Building the Right Product: Why, What, and How

- Christophe Dujarric

- November 17, 2025

Reminder: don’t trust fancy methodology names

I tend to repeat myself over all of the articles I’m publishing here, yet let me do it one more time for this particular topic: I don’t believe in dogmas.

I believe that many dogmas are more aspirational and theoretical than actual, factually implemented practices. Especially within the context of software delivery workflows.

I’ve had the chance to work with different attempted strict methodologies, whether it was Scrum, Kanban, XP, Spotify’s Model or Shape Up. All of which have seen at some point some thought leader publish a lentgthier or shorter blurb to tell how things should work. Should, not cloud. In fact, Spotify people themselves admitted later that their model was never fully adopted and had key flaws.

Let me stop here on this chapter, as you can read more about my thoughts on it in a past publication of mine.

There is yet one piece of writing, which could be considered a dogma but is more, in my opinion, a collection of sensible guidelines: the Agile Manifesto. The start of it all. Well, of many delivery frameworks, at least. If you still believe agility is about placing post-its on a wall, please go read this page.

What worked in the teams I worked with

What is clear is that we’re all trying to find an appropriate design and delivery workflow that still enables us to do some maintenance and find time for innovation. And as each and every of the fancy dogmas attempted to do that, each of them has interesting things to consider.

During my time at Traveldoo (an Expedia company building travel and expense management software solutions), we had a pretty decent implementation of Scrum. Yet, after trying for a while to apply it by the book, our team suffered from its rigidity and some irrelevant parts. So pretty much like the Agile Manifesto advises, we conducted some introspection, iterated and improved to find our own way.

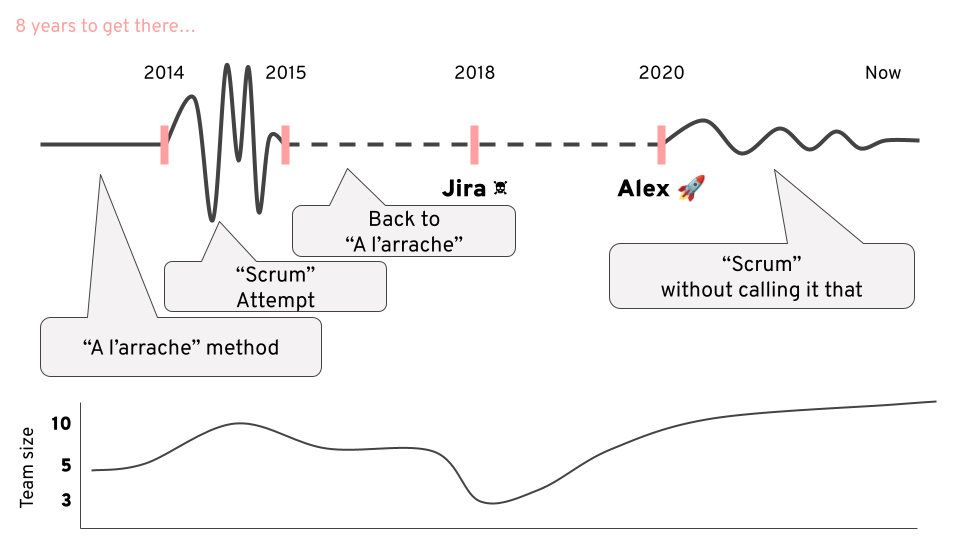

This was even more work at SensioLabs and Blackfire. When I joined, I was so happy about the framework I had implemented that I wanted to reproduce it. Believe me, I saw great engineers like Grégoire Pineau or Romain Viovi shaking in anxiety and frustration when I told them we’d start using Jira. Huge fail of mine. And huge learning curve. Over eight years, we iterated on our processes. And any time I would bring back any sort of Scrum-related vocabulary, I would see one of the engineers give me an angry look.

What finally worked was when Alexandre Salomé joined the team, and that we worked jointly on finding a simple way to express how to scope work and responsibilities. There’s a little more to that, but the core is in defining the Why, the What, and the How.

The Why

As a Product Manager (no matter what seniority or job title), this is your stuff. This is the aggregation and summary of your discovery, the vision and strategy, and the innovation (from a product perspective).

It says things very nicely, it is about why you want to build a given feature.

It gives all of the key context elements, justifies the value add, and hopefully sets some metrics that it should help your product achieve. It is a critical definition that should help developers understand why and when to prioritize developments related to that feature. It is your responsibility to have a very complete briefing, even though it is completely OK to miss some elements the first time you present it to the engineering team. It’s fine, just collect their feedback and questions, and iterate until it’s ready.

Drop the specs and user stories, drop the wireframes and mock-ups. It’s not the right time, it’s not the right place.

Where to write it? Up to you, really. It can be a Google Doc. A Confluence page. A ProductBoard card. We actually had that in ProductBoard, and in GitHub, as an intro to an issue that would help us track the progress on delivery.

The How

I hope you’ll excuse me for jumping straight to this one, as we still don’t know what we’re going to build, but I find it easier to start defining the extremes, the limits of the scope of responsibilities.

That part belongs to engineers (so you, if you were not the product manager reading the previous lines). Obviously, a PM won’t tell you how to code, design the architecture, build the infrastructure, select libraries, and tech components. It’s your expertise, and your judgement.

And to do your job with the appropriate resources, having a crystal clear understanding of the why is key. To make it stupid simple, you won’t build the same infrastructure for a load of a couple of hundred page views a month, or an LLM that will get requests from several thousand users a day.

Across iterations on defining and designing the “what”, we found a good practice in planning all of the tasks that would be necessary to completely deliver a given feature. Starting from the most critical tasks (such as provisioning machines), down to the least critical (changing the blue color of the design system for the 10th time in the year).

All of them would be listed as a checkbox list in the original GitHub issue. This is a very tactical advice, coming from the many improvements we’ve experiemnted with in the GitHub features, that made things much easier for us to deal with. Why do that? Because GitHub supports directly creating a PR from a checkbox list item, or linking to it, and will help track the overall delivery progress at the Epic, errr… issue level.

The What

Traditionally the part where there’s most of the dissension. Legacy of Waterfall practices, it’s usually the moment where Product Managers want to shine by describing in more or less detail how the feature will work, and what it will look like, eventually with the support of Product Designers.

It’s a ton of work, should it be done properly, since you’ll want to consider all edge cases and any impact it might have on existing product parts. You can end up spending weeks, even months in design.

And you’ll end up having to submit that to the engineering teams within a super large document they’ll never read, or a very short live presentation that will never let you cover all of the aspects.

And that is providing that you haven’t overseen anything, that devs’ hawk eyes will directly spot and let your Jenga game fall on the ground.

It doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t have given it some thoughts, nor drafted any description or wireframe; that gives a starting point.

But the what is clearly the place for collaboration between engineering and product management. Designing the what is an iterative process, so that from the first day, we avoid imagining rebuilding Facebook, when all you wanted was to post a note on a graph.

It is the moment where you’ll negotiate what is actually critical to achieve the why and related metrics, and what is just useless fancy stuff. You’re negotiating the 80/20. The 80% of the useful functional scope (hopefully done in the 20% of the time), so that you don’t waste 80% of the time on 20% of the useless stuff.

It is the moment when you can end up breaking down the original GitHub issue into multiple issues, if you realize some of the things you wanted to build don’t directly contribute to the why, but still might have an interest later down the road.

In practice

This article starts being lengthy already, so I won’t get into the exact details of how we build project boards, what tools we used to give what levels of detail in visual designs.

You’ll probably want to check the INVEST criteria, as this part was super useful for us to break down the work to be done, and reach an ability to estimate the workload to build a given feature, and obtain some roadmap predictability. Yes, that is possible.

I anyhow would not dare to write here one more of those fancy methods, even though in all humility I’m aware that my personal site doesn’t drive quite as much traffic as the Spotify blog.

The Why, the What and the How have been instrumental in helping us determine a proper design and delivery workflow, and clear responsibilities. I hope those basic principles can help you!

Note: the funny part is that over the years, we came down to a framework that was actually super close to Scrum, including delivery rhythm and rituals, even though we always made sure we wouldn’t use its vocabulary. And yet, it wasn’t Scrum. It was what made sense to our team, our product, and our company.